I visit southwestern Virginia regularly to see family and always end up looking around at old houses and suchlike. Lots of history around here, good and bad. Not a lot of money, generally, so old things tend to stay put rather than being torn down, tossed or made spiffy. For instance, this wonderful house near Fancy Gap, right off the Blue Ridge Parkway. Despite the issues, it seemed like it might still be occupied, or perhaps only recently vacated..

The porch and the trim with the little squares picked out have a folk-art quality; maybe that was a local style.

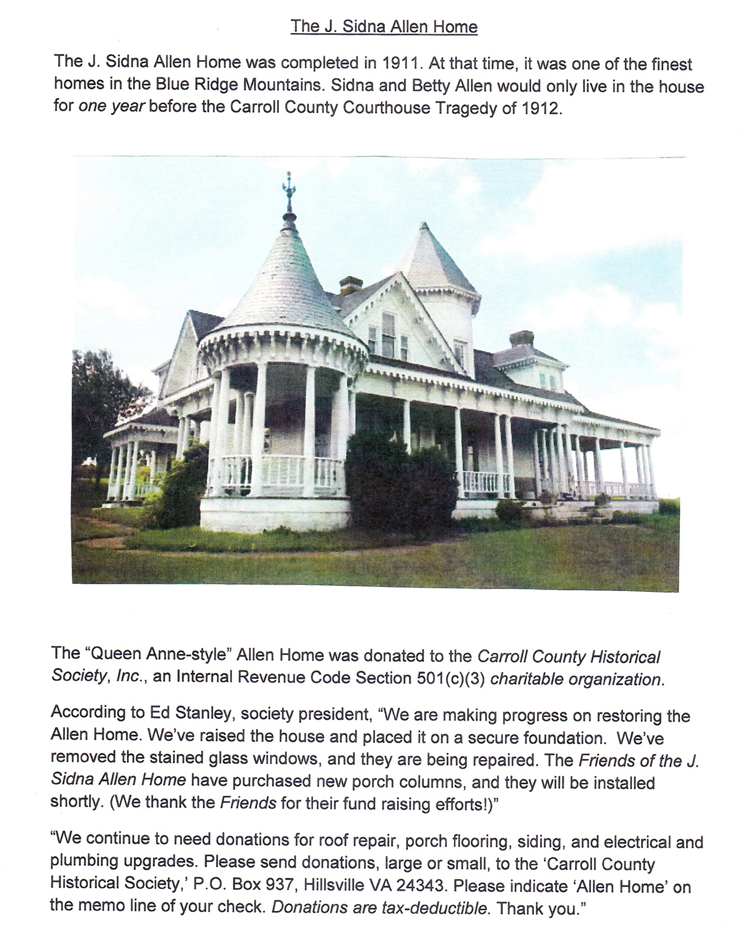

A much larger house on a rise overlooking the fields a couple of miles away has something of the same folk art feeling. I caught it mid-renovation, not looking it’s best. Still, it’s quite something to be driving up a country road bordered by fields, come around a curve and see this.

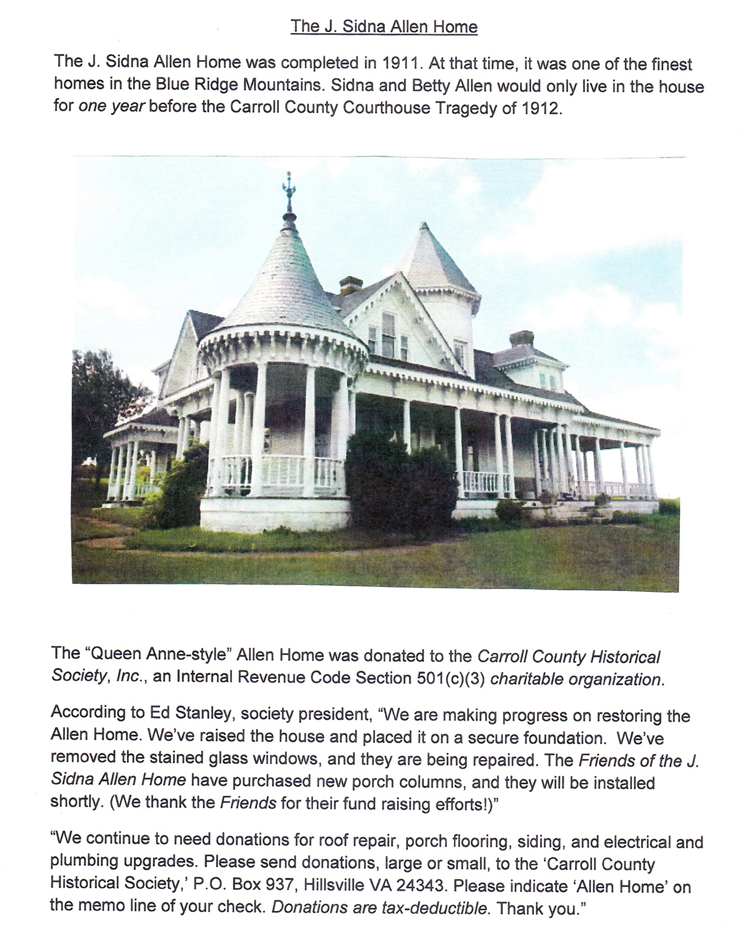

The house is asymmetrical, fairly simple in the basic structures, but on top of that the builder added windows of many different sizes, a tower (or is it a turret?), gables, multiple porches, a gazebo-like thing on one corner, lots of brackets and little notched trim along every edge. This house is sui generis.

I took these photos while standing in long grass on an uneven hillside, and later spent some time trying to rotate the photo to make it accurate, but some things just didn’t resolve — like that chimney. It has a gentle bend.

That wide cornice (?) on the porch is unusual and makes the columns look even more slender. I didn’t go up onto the porch, but here’s the view from the road in front of the house, which must look much the same as it did a hundred years ago.

A house like this must have a story and sure enough, this one does. Nailed to a post across from the house was a plastic folder with several copies of this flier:

Someone who lives in a nearby town told me that this area was a bit like the Wild West in those days; most people drank a lot, everyone had guns and there were feuds, both family and political. People got shot all the time. The Carroll County Courthouse tragedy of 1912 mentioned on the flier is a fascinating story, one that made international news at the time it happened.

Someone who lives in a nearby town told me that this area was a bit like the Wild West in those days; most people drank a lot, everyone had guns and there were feuds, both family and political. People got shot all the time. The Carroll County Courthouse tragedy of 1912 mentioned on the flier is a fascinating story, one that made international news at the time it happened.

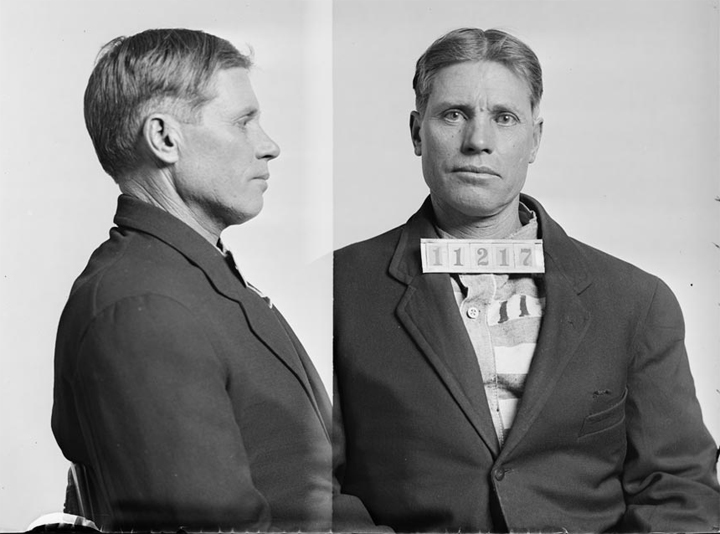

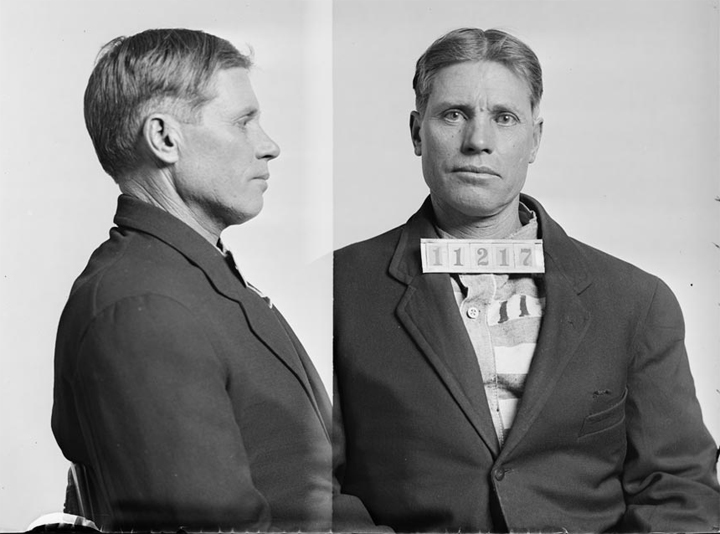

(Here’s Jeremiah Sidna Allen, the man who built this house, and yes, that’s a mug shot)

(Here’s Jeremiah Sidna Allen, the man who built this house, and yes, that’s a mug shot)

The story has been well-told elsewhere, but here’s a quick version: J. (Jeremiah) Sidna Allen’s brother Floyd was a farmer, shopkeeper and moonshiner, famous for his temper. After his nephews were arrested for fighting (someone kissed someone else’s girlfriend) and taken by wagon to the jail. Floyd intercepted the wagon, beat the deputy and freed his nephews. He was arrested for assault and interfering in an arrest and was put on trial in the courthouse in Hillsville. Members of his family, including Jeremiah, brought their weapons that day and when the verdict of one year in jail was read, Floyd refused to go. The courtroom erupted in a gun battle. When it was over, the judge, the prosecutor, a juror, a witness and a sheriff were dead. Some of the Allens, including Floyd, were captured immediately; others, including J. Sidna, escaped.

(The house around the time of the Courthouse tragedy, photo from this blog)

(The house around the time of the Courthouse tragedy, photo from this blog)

There was a big manhunt and the story was in the news for weeks (only displaced by the sinking of the Titanic). Floyd and his son Claud were convicted and executed for their part in the massacre. J. Sidna and other family members got jail sentences and were later pardoned. Later in life, . Sidna supported himself in part by telling his family’s side of the story and selling his woodwork. He was quite talented, as his fanciful house shows.

Fancy Gap is still a small community, not quite a town, with less than 300 people. I usually stop at the Pottery and Fabric Outlet when I come through; it’s housed in a couple of wood buildings right off the parkway. I didn’t get photos, except for this old carriage outside, but here’s their website so you can get an idea.

It’s definitely worth a visit. The pottery outlet has hundreds of glazed plant pots in all sizes, plus birdbaths. The pots are seconds but still quite good and the prices are maybe a third of similar stuff at a big box store. Inside, there’s a lot of home decor items, mostly very country or old time-y style. I got these simple iron hooks for $2.09 ea. They’re rough, but they’re going in the basement storeroom, so that works.

A little over an hour north and east is Salem, a much bigger town. We were just driving through when I glimpsed a mansard roof on a side street and had to check it out.

This is North Broad Street, where the folks with money lived — still live, given the level of maintenance it would require to keep houses of this age in such good condition. There are houses of many styles here, from the 1880s to the 1950s, all set back on large lots.

Of course this one caught my eye — I love mansard roofs. This is an example of the Second Empire style (that’s the reign on Napoleon II) was, which popular from about 1860 – 1880. The roof and the arched windows are the most recognizable elements of that style.

According to A Field Guide to American Houses, Second Empire homes were relatively rare in southern states. This one is also interesting in that aside from the roof and the ornate trim, it’s a rather simple brick building.

Shutters inside and out! (And a humble touch that reminds me of my own house: the plastic extender on the downspout.)

This lovely Queen Anne is right across the street. Like other houses on this street, it’s beautifully kept, as if it was never permitted to fall into disrepair.

That porch!! It makes so much sense that the most ornate part of the house would be the area where people will be able to see it up close. Even the screen doors and the mailbox are just right.

And such a good color scheme — there are at least five colors on this house, but it’s so well thought-out that everything harmonizes, nothing leaps out. Whomever came up with these colors really knew what they were doing.

There’s something so satisfying about seeing the same level of care and detail on the side of a house. And check out those cornerboards, picked out in the darker yellow, which help define the structure and visually break up large areas. So nice. Even the garage, just visible back there, got the same treatment.

Right next to that, a different approach on a smaller, less ornate house. Sometimes a very simple color scheme is just perfect.

It’s nice that the addition is smaller and behind the main structure, and that both addition and deck are the same color/style, so the original house remains the focus. I’m not so sure about the cresting (that little iron fence) on top of the bay window. The proportion looks off, it seems too big for that little bit of roof. I wonder if it’s original — if so, there would also have been cresting up along the roof peak. Still, cresting doesn’t seem right for the style of the house, which is more simple. Maybe that little bit was added more recently, to dress up the side of the house. Who knows? Most 19th century houses were very much mix-and-match, style-wise.

Back on the other side of the street, another simple pale color scheme on a much larger house.

The color isn’t historically accurate for a house of this period, but it’s really nice; the body and the trim are tonally close, with just enough difference to pick out the trim details and accentuate the structure. Subtract the porch and the bay window and this is clearly an Italianate style house, probably built in the 1870s. Although the roof is different, the basic shapes and proportions of the facade are quite similar to the brick house above. I’m guessing that lovely front porch and the central bay window above it were added 10- 20 or so years after the house was built, to update it a bit.

Subtract the porch and the bay window and this is clearly an Italianate style house, probably built in the 1870s. Although the roof is different, the basic shapes and proportions of the facade are quite similar to the brick house above. I’m guessing that lovely front porch and the central bay window above it were added 10- 20 or so years after the house was built, to update it a bit.

With so many beautiful houses in a small area, I know this town must have other great houses and buildings, but we were just passing through and didn’t have time to properly explore. I hope to come through again with more time and see more.

(linoleum rug, found upstairs when removing wall-to-wall carpeting)

(linoleum rug, found upstairs when removing wall-to-wall carpeting)