This might seem like a divergence from the topic of old houses, but it isn’t really. An old house — any house — isn’t separate from its location. It’s part of a neighborhood, a city, a region; subject to the same environmental issues, forces of politics and commerce as everything else.

Like thousands of other Pittsburgh area residents, I live near railroad tracks. In a lot of cities railroad tracks are more on the edges of town, but here trains snake through densely populated areas, right through the center of the city. There are five different sets of tracks just below my house; there used to be a lot more.

I’ve always liked trains; traveling on them, living somewhere I could hear them, but it took a couple of years after we moved in to get used to just how loud it can be when you’re close by. The rumble of trains shakes the hillside, their horns mark the rhythms of the day and night. Did you know that each engineer has their own particular horn pattern? I don’t need to look out the window to know that Amtrak is coming through, or that the dark red and gold locomotive is pulling past the warehouse down below, as it does most weekday afternoons. There’s a long, high-pitched squeal as trains round the curve a few blocks east. As the locomotives slow down the cars slam into one another, the first CRASHBOOM so loud the impact vibrates the hillside, then BOOMBOOmBOomBoomboomboom, fading down the line. When I’m outside working in the yard and a freight train goes by, the thunder of it fills the world.

What I didn’t learn until a couple of years later is that among the trains that pass through Pittsburgh each day, some of them, long trains of black tankers coming from the west, are carrying highly volatile crude oil from the Bakken shale in North Dakota. About 25 trains carrying crude oil, 40 -50% of all the oil going to refineries in the East, pass through Pittsburgh each week. This is a fairly recent development; it wasn’t until 2012 that rail shipments of crude oil began to dramatically increase. These trains are traveling on lines that were built to carry things like coal, lumber and agricultural commodities; they were never intended to carry such dangerous cargo.

Of course, not all tankers carry crude oil, they might contain other materials; anything from corn syrup to ethanol. If the contents of a tanker are hazardous there will be a red diamond-shaped sign on the side, with a number on it. (The number for crude oil is 1267.)

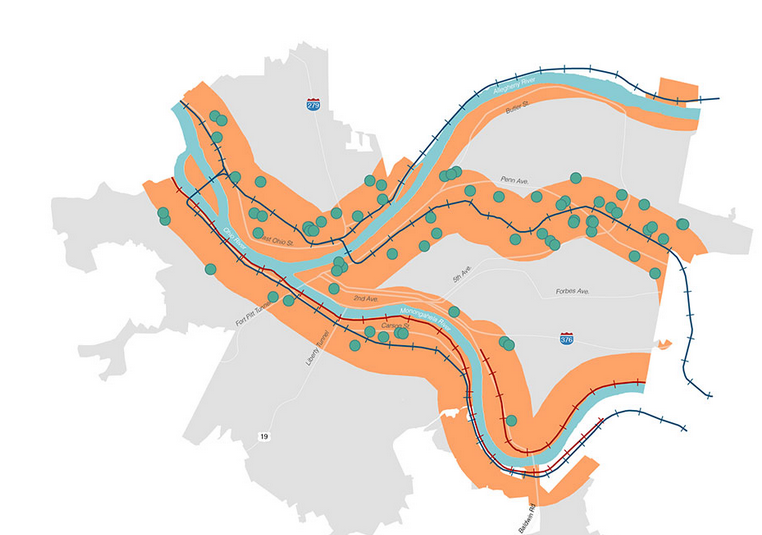

This isn’t just my problem; forty percent of Pittsburgh residents live within the half-mile federal evacuation zone in case of a derailment. That’s much of downtown and the Strip District, almost all of Polish Hill, parts of Bloomfield, North Oakland, Shadyside, East Liberty, Point Breeze, Homewood, Wilkinsburg, Edgewood and communities further out. Public Source created a map showing the derailment danger zones around the railroad lines that carry crude oil through Pittsburgh. (The orange areas are the danger zones, the blue dots are schools.)

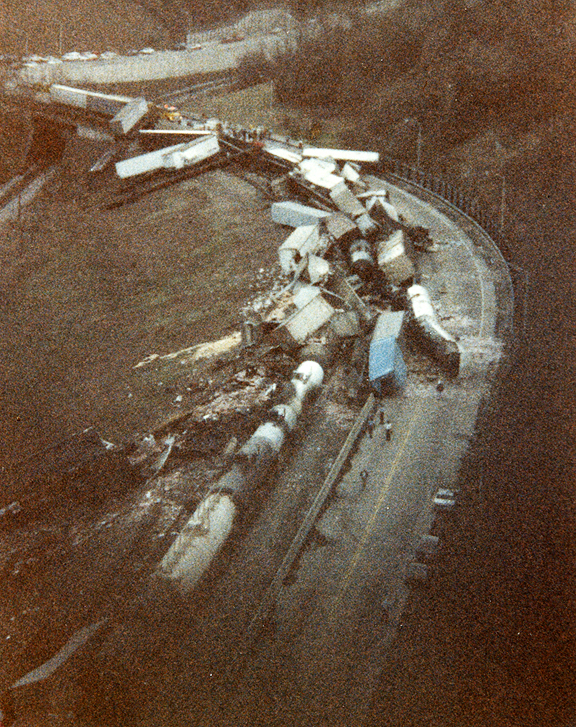

The prospect of a train derailment near my house isn’t just theoretical. That curve a few blocks east, where trains squeal as they round the curve? That was the site of a derailment in April 1987 of a mixed freight train which included a number of tanks of hazardous chemicals. One car, containing phosphorus oxychloride, ruptured and leaked. 16,000 residents were evacuated but fortunately there were no serious injuries. Again, that was just one car, and the contents were not flammable.

If a crude oil train derailed and just one tanker caught fire, the outcome would be much different. This type of fire is too hot to extinguish; anything sprayed on it just evaporates. The protocol is to evacuate everyone and let it burn — for days — until it cools down. Living in an old wood-frame house on a windy, brush-covered hillside makes this a scary thing to contemplate.

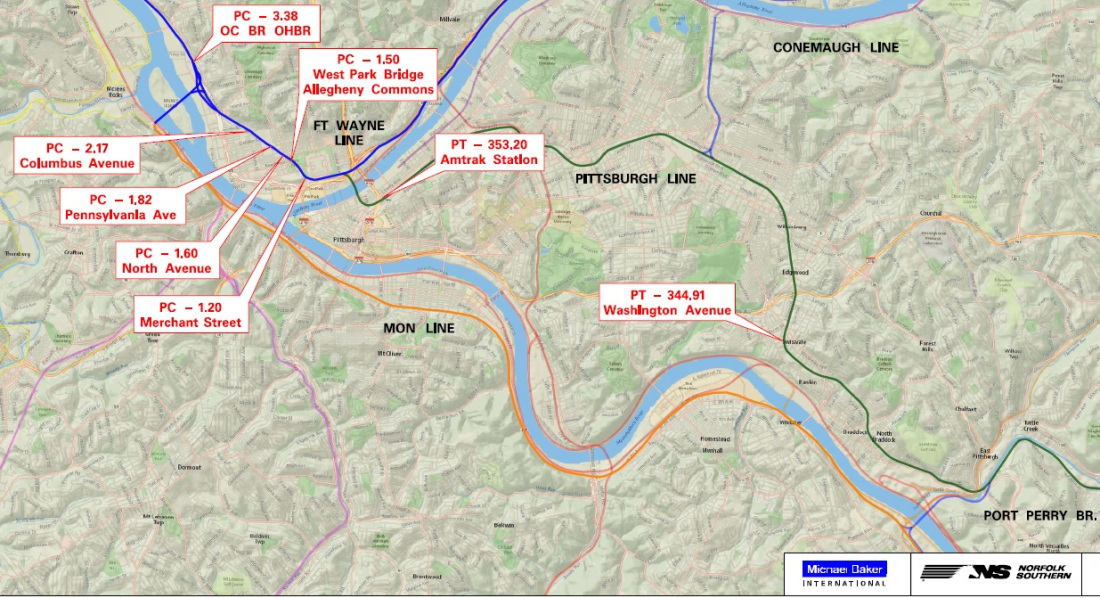

Now I’m learning that Norfolk Southern Railway, which owns three of the railroad lines that run through town — including the Pittsburgh Line that runs through the Northside, Downtown, and the center of the East End — plans to greatly increase the amount of cargo they transport through Pittsburgh. The company has already started increasing the length of trains (from a max length of 1.5 miles up to 3 miles long). They plan to double the number of trains that will come through (item #6 in the linked document). And they have a plan called the Pittsburgh Vertical Clearance Project, which involves raising nine bridges along the Pittsburgh Line which are too low to allow double-stack trains to use this line. Double-stacked trains currently only run along the Mon Line, along the base of the hill in the South Side.

Adding double-stacked trains to the Pittsburgh Line would compound the issues of pollution and noise that already exist. The possibility of a derailment is just that — a possibility; the problems that double-stacked trains will bring are certain. Increasing train volume by introducing double-stacked trains will produce more pollution in densely populated neighborhoods and that pollution is concentrated in areas closest to the tracks. Double stack trains have a higher center of gravity, are therefore more unstable –especially when empty. And although double stack trains don’t carry crude oil yet, they will run alongside trains that do, which could increase the chances of a serious derailment and chain reaction explosions. In addition, much of the Pittsburgh Line through Pittsburgh is curved, not straight (derailments are more likely on curved tracks). The most recent derailment in Pittsburgh, on the South Side in August 2018 was a double-stacked train; the cause was a broken rail line.

Thus far, public attention on the Pittsburgh Vertical Clearance Plan has focused on the North Side, where five of the bridges Norfolk Southern wants to raise are located. But impacts from double-stacked trains and increasing rail traffic would affect everyone who lives along the Pittsburgh Line — about 112,000 people. Here’s a partial list of the places closest to the Pittsburgh Line, where these impacts would be greatest:

Northside (Heinz Field, PNC Park, Allegheny General Hospital, NRG Energy)

Downtown (around the convention center, the Westin Hotel, the Greyhound bus station)

Strip District (the tracks run parallel to Liberty Avenue, two blocks from the main shopping street)

Polish Hill (the entire length of the neighborhood)

Bloomfield (the southwest section, ie. Lorigan and Juniper Streets and areas near the Bloomfield Bridge)

Shadyside (Baum Boulevard,residential areas around S. Millvale, S. Aiken and S. Negley; the UPMC Shadyside campus; the trains run parallel to Centre and Ellsworth avenues, then go under Penn and alongside Target and Trader Joe’s)

Point Breeze (alongside Westinghouse Park and behind Construction Junction)

From Point Breeze, the line passes through Homewood, the edge of Regent Square, Wilkinsburg, Edgewood (behind the Towne Center Giant Eagle), Swissvale, through the center of Braddock and beyond.

In the last five years Norfolk Southern has greatly increased the amount of hazardous cargo it brings through Pittsburgh. They have made trains longer. Now they’re working to implement a plan that will double the number of trains they run and how much cargo those trains carry. Currently the Pittsburgh line carries about 25 trains a day; but it’s capacity is about 70 trains a day — which would mean virtually constant rail traffic, noise and drastically increased pollution. It’s easy to see how increasing rail traffic will benefit Norfolk Southern’s owners and stockholders, but not why their private interests outweigh the public interest and the costs to tens of thousands of Pittsburgh residents who live along these rail lines.

Obviously crude oil and other goods are going to be moved; it’s also clear that increased rail traffic will affect people, it’s just a question of where and how many. According to Pitt researcher’s estimates, adding double-stacked trains to the Pittsburgh Line would impact more than twice as many people as would be affected by more traffic on the Mon Line. It would seem to make more sense to make sure that as few people as possible are impacted.

Pittsburgh already has an air-quality problem. If Norfolk Southern is successful in all aspects of their plan, impacts from rail traffic through Pittsburgh will impact large swaths of the city with more air pollution, more noise and vibration and a higher likelihood of a serious derailment incident in a densely populated area. This would affect not only the 40% of residents who live near train tracks, but also property owners, developers and other stakeholders who have an interest in the revitalization of the city. Blocking Norfolk Southern’s plan to raise the bridges will head off a host of problems that would harm Pittsburgh residents for years to come.

——-

UPDATE: In May 2022, Norfolk Southern and North Side community groups came to an agreement whereby the railroad can raise the bridges and the North Side community groups would get 2 million to offset impacts to the community. City Council voted to accept this agreement, opening the door to double-stacked trains to run through Pittsburgh.