(photo courtesy of David Bakaj)

Here’s my house in about 1947 (going by the license plates). It’s the one in the background on the right, with the little pediment roof over the front door. That pediment was new, aluminum supported by simple black iron brackets — a popular 40s style update. The window trim has been removed so that dark red asphalt shingle siding could be fitted over the wood clapboards. The house to the left, built around the same time but not yet updated, still has the style of a bygone era.

(original 1870s wallpaper in the upstairs hallway)

A good friend gave me a wonderful housewarming gift: a house history by Carol Peterson, which came in the form of a folder of maps, copies of deeds, and newspaper notices. Carol compiled this material from research in public records and wove it together to tell the story of the original owners. Below is her summary about the people who built the house and those who lived here subsequently, with my photos of house details.

James C. Rayburn Jr. and his wife, Hannah Dain Rayburn, had [the house] constructed between 1872 and 1873. The house was built on part of a double lot that Hannah D. Rayburn had purchased in 1871, for $1100.

James C. Rayburn Jr. was a bookkeeper and clerk with Armstrong and McKelvy, a paint company, during the time that he and his family lived [in the house]. He lived during much of his childhood on Penn Avenue in the Strip District, where his father was a Pennsylvania Railroad foreman and president of the neighborhood school board. Hannah Dain Rayburn also grew up in the Strip District. Her father was an Irish immigrant who ran a livery stable, and her mother was a Welsh immigrant.

The Rayburns were in their early 20s with two small children when they moved into the new house. They eventually had eight children, all of whom lived in the house. Hannah Rayburn’s mother Hannah Dain also lived [in the house] from the time that the house was built until she died in 1884.

In the early 1890s, the Rayburns moved to South Winebiddle Avenue. They owned [the original house] until 1896, renting the house to tenants.

(small objects found during renovation)

A section of brief notes brings later residents into view, sketching out the story of the neighborhood as well as the house.

1900

The 1900 census enumerated the Gallagher and Greenawalt families living in apartments at [the house]. James Gallagher, 43, was a day laborer who had immigrated from Ireland in 1873. His wife Julia, 36, had immigrated from Ireland in 1876. The Gallaghers had been married for 20 years and had nine children. Seven of their children were living: Edward, 19, a day laborer in a mill, Margaret, 16, a packer in a cracker factory, James, 13, Ellen, 11, Mary, six, Sarah, four, and Julia, one.

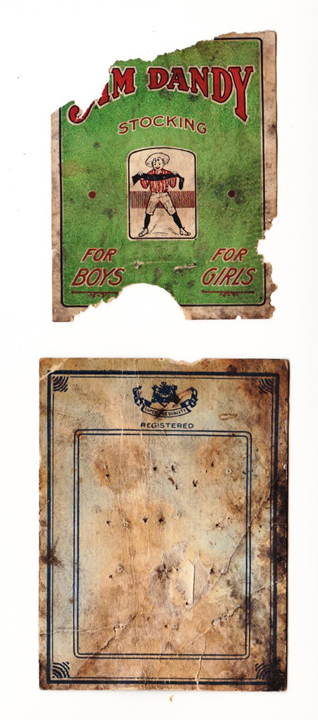

(labels found in back of a closet on the first floor)

William H. Greenawalt, 34, and his wife Jennie M., 33, rented the other apartment. Both were at least second-generation Pennsylvania natives. William Greenawalt was a blacksmith’s helper. The couple had been married for ten years and had three children, two of whom were living: Clyde A., eight, and Jennie B., seven months.

1910

Records of the 1910 census do not identify occupants of [the house].

(Fragment of a comics page from 1911, found stuffed in a wall)

1920

In 1920, the Raschle and Kaylor familes lived [in the house]. Albert and Sophie Raschle were both 29-year-old Polish immigrants. Albert had immigrated in 1909, and was a hammerman in a forging plant. Sophie had immigrated in 1912. Neither had learned to speak English. Their children were Albert, six, Olga, four, Arthur, three, and Edward, one.

(linoleum rug, found upstairs when removing wall-to-wall carpeting)

(linoleum rug, found upstairs when removing wall-to-wall carpeting)

Mary Kaylor, 35, was divorced and worked as a car cleaner in a railroad yard. She had been born in Pennsylvania to parents born in Alsace-Lorraine and England. Her daughter Margaret, 16, was a buncher in a cigar factory. Catherine Negley, 24, was a sister of Mary Kaylor and a widow. She lived with the Kaylors, and was also a railroad car cleaner.

(ruler from a local shoe store, found behind a baseboard)

1930

Polish immigrants Piotr and Mary Kozlowski owned and lived [in the house] in 1930. Piotr Kozlowski was a rail car cleaner. Census records show that the Kozlowskis had learned to speak English, but neither could read or write. Their children Tadeusz, 13, Waclaw, 11, Raymond, nine, and Edward, four.

Vincent and Frances Przyeck rented an apartment at [in the house]for $15 per month. Vincent, 25, was a laborer in a rivet factory. He and Frances, 23, had been born in Pennsylvania to Polish immigrants. They had been married for two years and had no children. Michel Olnicki, France’s widowed father, lived with the couple. He spoke English but could not read or write.

Information about past residents ends there. Carol noted, “Manuscript census records are withheld from public view for 72 years, to protect the privacy of persons who were enumerated.” After living in this neighborhood for over ten years, I’ve gotten to know several other people who lived here and learned a little bit about their stories.

(layers of floor coverings in the upstairs kitchen)

I came to think of the previous residents of this house as neighbors, separated by time instead of distance. They made food in the same kitchen, maybe put their bed in the same spot. They were also awakened by the train whistle and the boom of freight cars shaking the hillside. They slept, or tried to, when storms shook the house. Maybe they also put a chair in front of the window that catches the breeze from the north in the summer.

(upstairs sitting room)

Reading about my neighbors-in-time is a reminder that although I’m here now, like them, one day I will leave and not come back. In art this understanding can be prompted by a memento mori, an object/idea which provides perspective and some wisdom by reminding us of the impermanence of life. Maybe all histories work that way, but Carol’s house history is also about change and renewal through the narrow lens of one simple wood house and the people it sheltered.

Carol died in December 2017. She’s missed. As a historian she believed that the history of working class people was worth preserving, including their homes. She bought old houses herself and with a series of light-handed renovation projects she proved that it’s both financially feasible and market-friendly to preserve old houses, rather than gut or demolish them. She created the Pittsburgh House Histories Facebook page, which her friends are maintaining, to make this point. She co-wrote (with Dan Rooney) Allegheny City: A History of Pittsburgh’s North Side. She was a tireless advocate for the value of historic preservation, which is how I met her. She wasn’t afraid to stand up and ask uncomfortable questions at public meetings. And she did house histories, hundreds of them. Many homeowners in Allegheny West who got house histories from Carol shared them for this online archive.

(Carol’s own house in Lawrenceville, one of her restorations.

Photo from this blog)

If you’d like to know more about Carol, here’s an article about her house histories. Here’s an article about her work as an architectural historian. And here is the appreciation of her life and work in the local paper.

Thank you, Carol, for all that you did.